In a 2017 collaboration among multiple American and European COPD research groups, we assessed the reproducibility of multiple clustering approaches and PCA in ten independent cohorts. This project remains one of my favorites, because the result was surprising and important. The published paper is fairly dense and complex, so the point here is to distill the essentials from that work. The primary goal of the project was to discover clusters that were replicable across all of our participating cohorts. For the clustering methods, we used the approaches described by Horvath and Langfelder, which are extensions of k-mediods and hierarchical clustering.

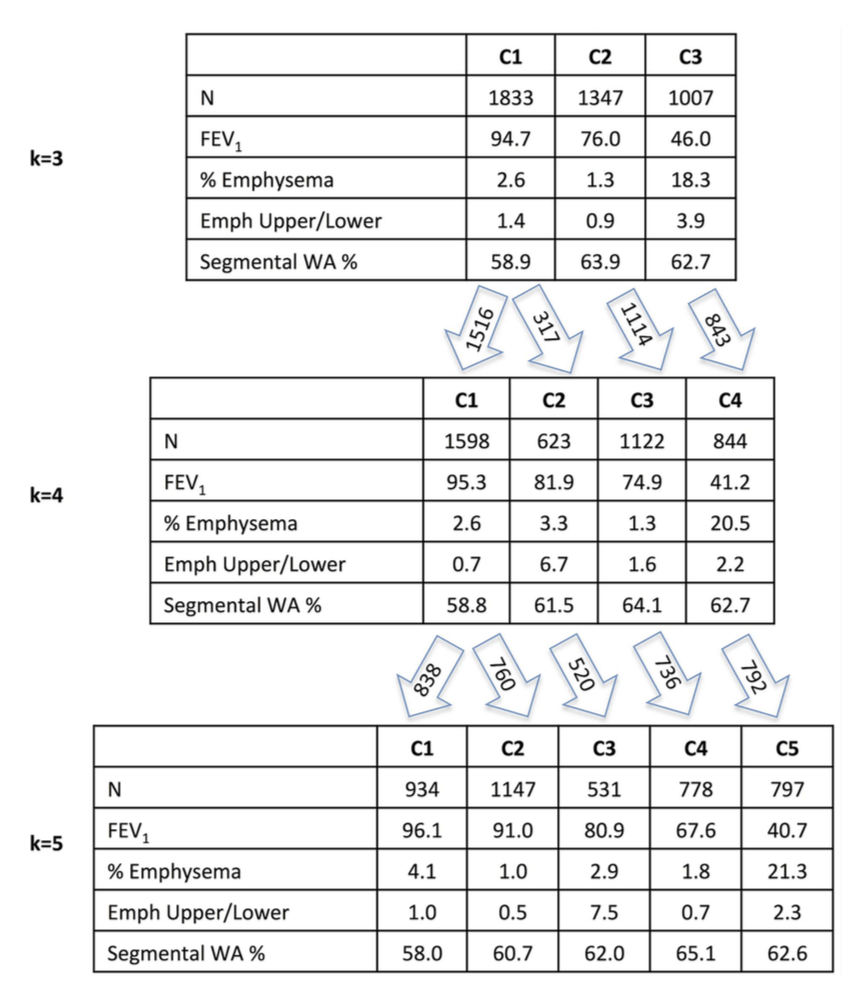

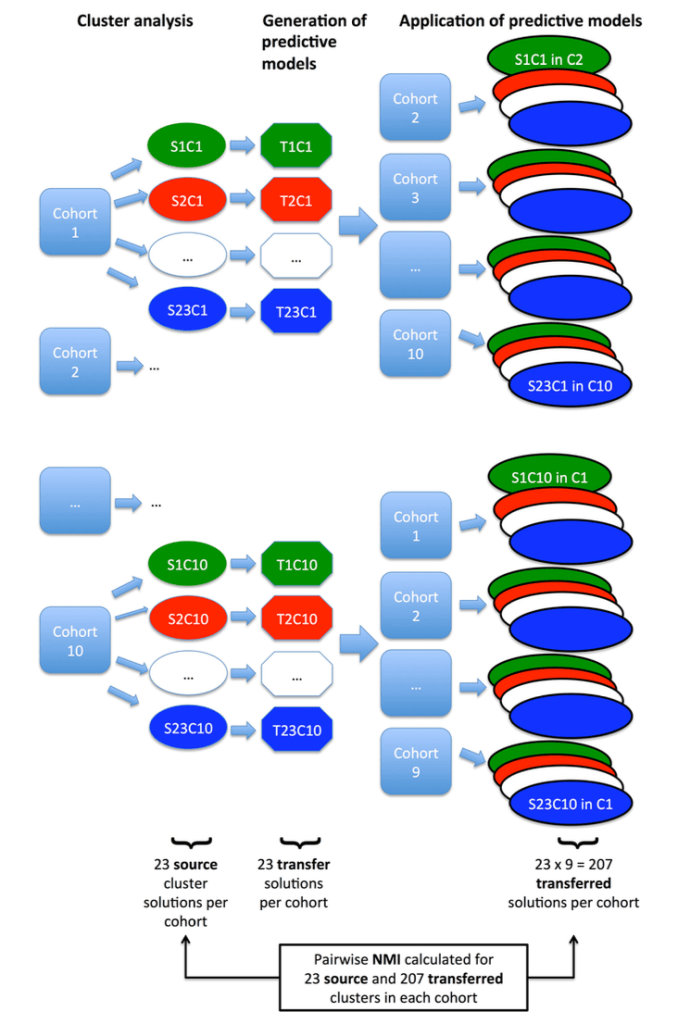

Since the choice of clustering parameters is often critical for the final results, we systematically varied k, minimum cluster size, and other more complex parameters for pruning the resulting hierarchical trees. This resulted in 23 clustering solutions within each of the 10 cohorts. The next challenge was how to compare these clustering results across studies. To do this, we built supervised prediction models in each dataset to predict the cluster membership for each of its 23 clustering results. These predictive models were then shared between the groups to “transfer” clusters from one cohort to another. This allowed for all of the 230 (23 solutions x 10 cohorts) clustering solutions to be compared within each cohort. The schematic of this workflow is shown below.

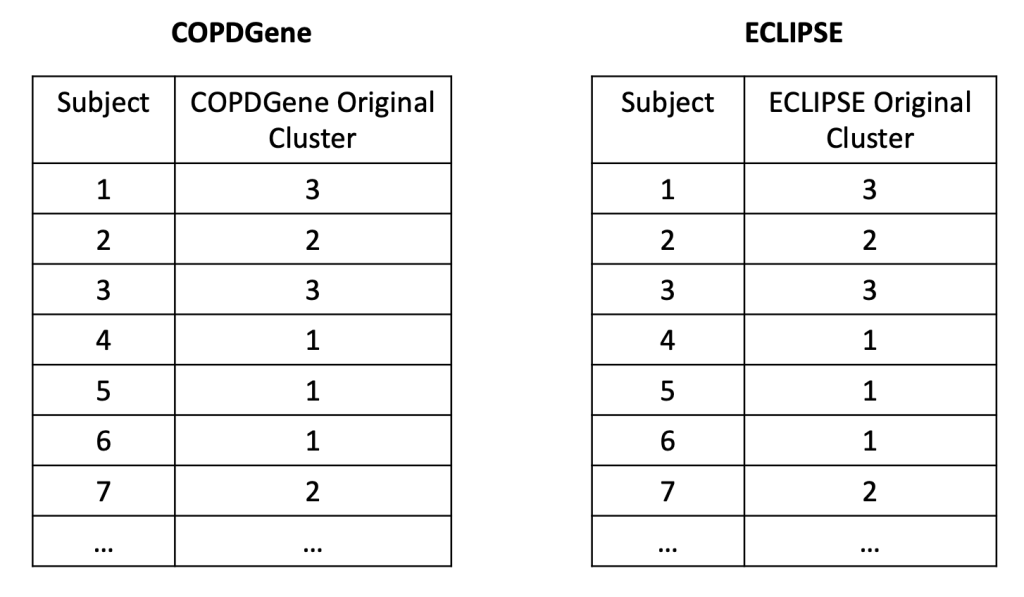

So what did we find when we compared these clustering results? A disappointingly low level of reproducibility. To give a specific example of what reproducibility means here, imagine that we generated two clustering results using the exact same methods, variables, and parameter settings in the two COPD cohorts, COPDGene and ECLIPSE. In each cohort then, we have an “original” clustering result, that looks like this.

In each cohort, we then build a predictive model to predict cluster membership. We trade models between groups, and we end up with the ECLIPSE clusters in COPDGene and vice versa. So now the cluster assignments look like this.

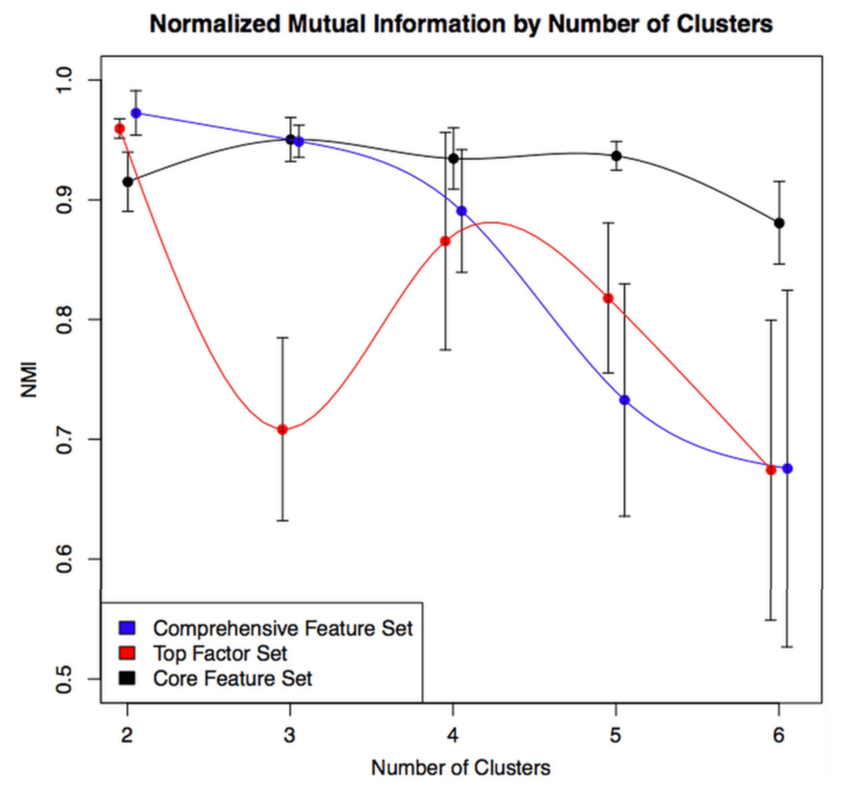

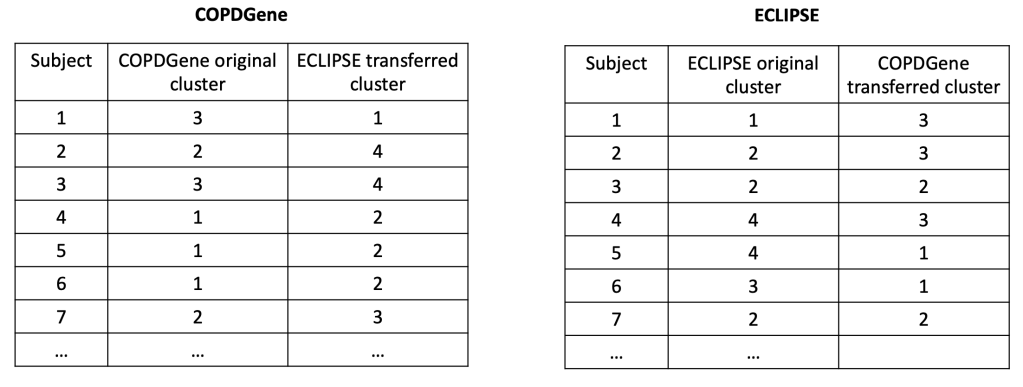

So, using the same subjects in each cohort, we can now look at the concordance between cluster assignments. If you consider things from the point of view of just one cohort, you now have the 23 original solutions from that cohort, as well as 23 x 9 = 207 transferred solutions from the 9 other cohorts. For each original solution, you could then compare it to its 9 exact matches from the other cohorts, or you could just compare it to every single transferred clustering solution to look for the best match. As our metric of similarity we used normalized mutual information (NMI), which gives a value of 1 for a perfect match and a value of 0 for completely independent solutions (some potential limitations of NMI are mentioned here). In our analysis we did the comparison both ways, and no matter how we looked at it the results were a bit disappointing. You can see the distribution of NMI values for each of the participating cohorts here.

To sum this up:

- median NMI is almost always below 0.5. Not great agreement.

- We divided clustering methods into groups, and the red group always has higher NMI values (groups described below).

- Most cohorts have a handful of very reproducible solutions. But when we compared the high NMI solutions across all cohorts they were inconsistent (i.e. different number of clusters, no consistent high NMI performer across all cohorts).

The blue, green, and red bars indicate the three different general classes of clustering that were used. Blue = k-medioid clusters. Green and Red = hierarchical clustering. Importantly, on the red group of clustering solutions had the option of defining subjects as “unclusterable.” Thus, only the red methods have the option of saying, “I refuse to cluster some proportion of the subjects in this dataset.” For the details of these clustering methods you can refer to the brief paper by Langfelder and follow the citation trail as far as you want.

So if the clustering reproducibility isn’t great, the first three explanations that come to mind are as follows:

- the algorithms stink (probably not the case since these have been shown to work with other kinds of data)

- the cohorts are just very different from each other

- the cohorts are similar, but there aren’t any clusters

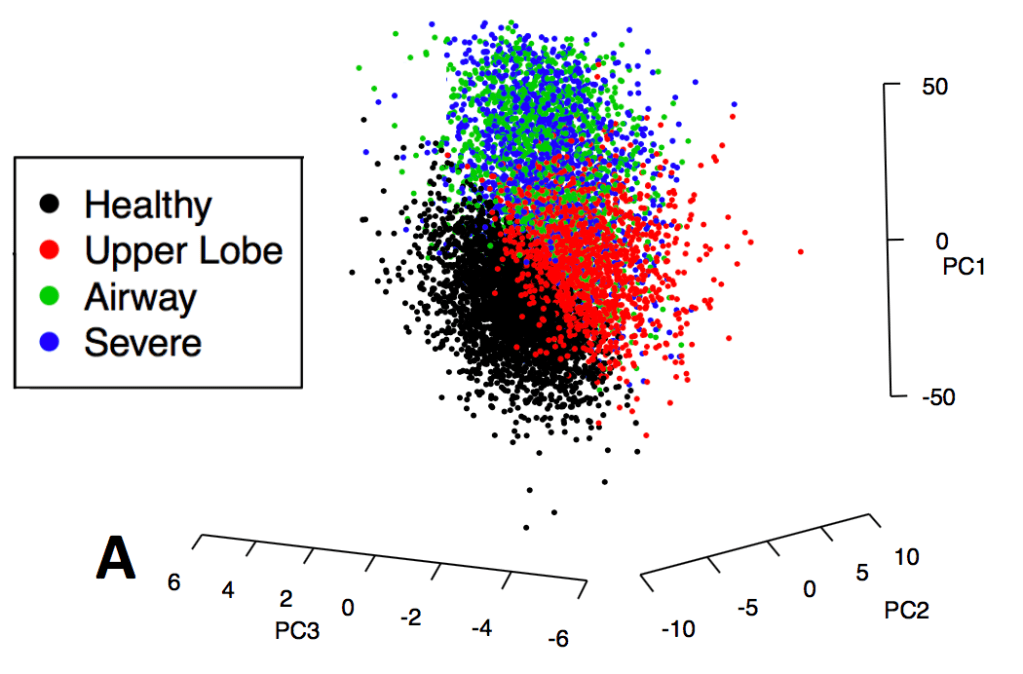

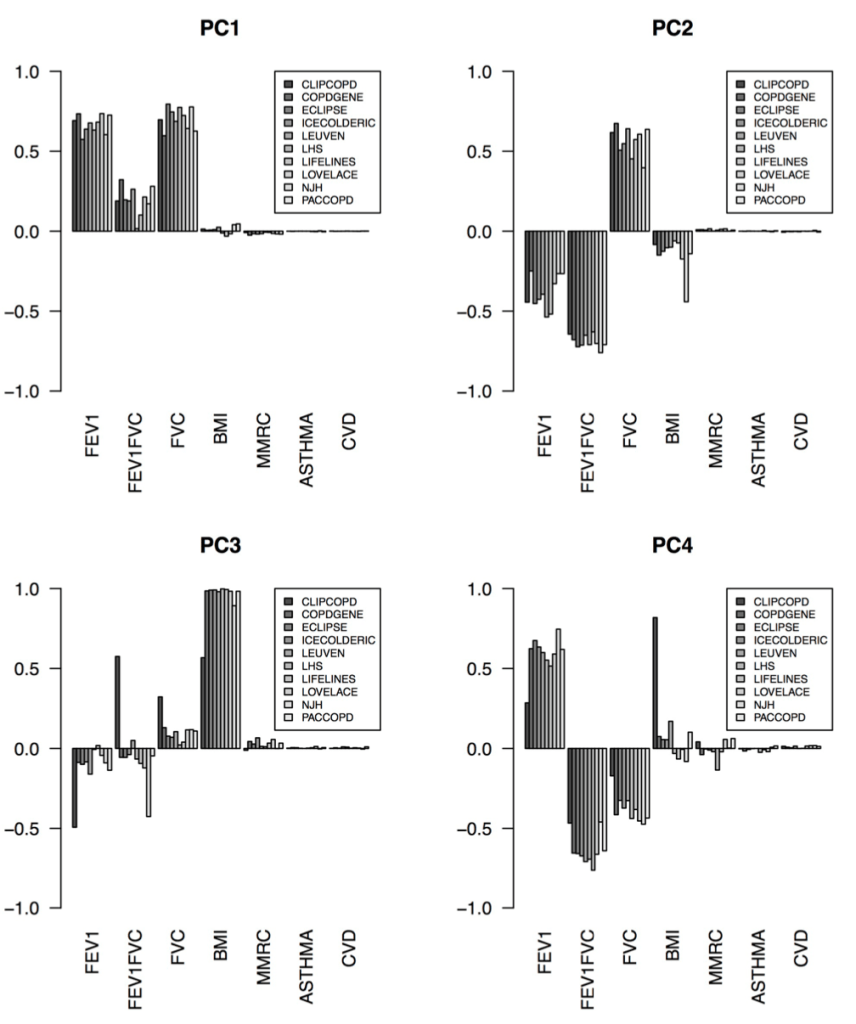

The correct answer seems to be the third one – the cohorts are actually fairly similar, but the process of defining clusters is what is not reproducible. The observation that supports this is that, when we calculated principal components from the same data used for clustering, the principal components were extremely similar. Here are the variable loadings for the first four PCs in each of the participating cohorts.

So, bad clusters, good PCs. The most natural conclusion is that the cohorts are in fact very similar, and more specifically the covariance structure of these variables is very consistent across cohorts. But the clustering partitions in these cohorts are not reproducible, probably because there is no “good” place to draw dividing lines in these data. The take home message is that we should probably focus first on PC-like continuous dimensions of variability (disease axes) rather than jumping immediately to clustering algorithms.